It Took Thousands of Personal Stories to Create the Mariner 9 Story

Fifty-four years ago today, on May 30, 1971, a symphony of human ambition lifted off from Cape Kennedy. Mariner 9 wasn’t just a spacecraft — it was the culmination of thousands of individual stories, each person contributing their unique thread to a tapestry that would forever change how we see our place within the cosmos.

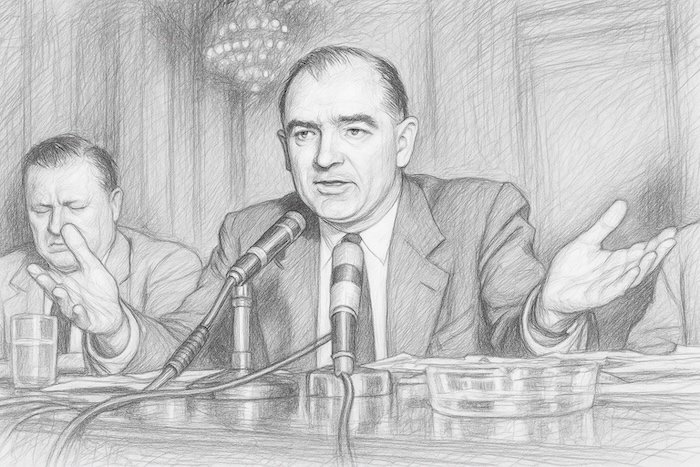

Launch of Atlas-Centaur Rocket Carrying Mariner 9 Mars Probe

The Genesis of a Dream

The Mariner program began in 1962, nine years before the launch of Mariner 9. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory conceived this series of robotic explorers as stepping stones to the planets. Each mission built upon the last — Mariner 2 had whispered past Venus, Mariner 4 had glimpsed Mars in passing. But Mariner 9 would be different. It would stay, orbit, & see.

The development of Mariner 9 took approximately four years of intensive work, from initial design concepts in 1967 to its 1971 launch. Yet this timeline barely captures the human drama unfolding behind the scenes — engineers working through weekends, mathematicians recalculating trajectories late into the night, technicians hand-assembling delicate instruments with the precision of watchmakers.

A Cast of Thousands

Picture this: over 5,000 people directly involved in the Mariner 9 mission, with countless more supporting roles spanning across multiple states. From the assembly floors of Denver to the tracking stations scattered across the globe, this was humanity at its collaborative best. Each person — whether they wielded a soldering iron or a slide rule — contributed their personal skills and passion.

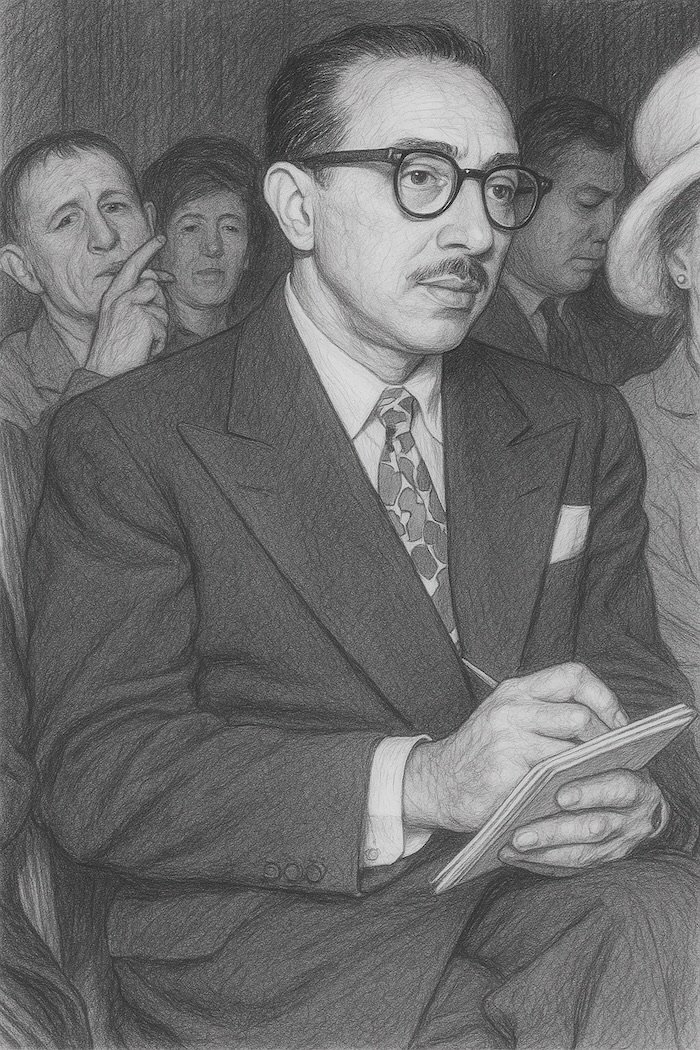

Mariner 9 Mars Probe

The mission required an extraordinary convergence of skills, including:

- Aerospace engineers designing the spacecraft’s structure

- Propulsion specialists calculating fuel requirements

- Computer programmers writing navigation software

- Antenna technicians ensuring Earth-Mars communication

- Planetary scientists planning observation sequences

- Materials experts selecting heat-resistant components

- Optical engineers crafting camera systems

- Electrical technicians wiring complex circuits

- Systems integrators coordinating all subsystems

- Project managers orchestrating timelines

- Quality assurance inspectors checking every detail

- Mathematicians computing orbital mechanics

- Thermal engineers managing temperature extremes

- Power systems designers creating solar panel arrays

- Attitude control specialists maintaining spacecraft orientation

- Data analysts interpreting incoming signals

- Mission planners designing observation strategies

- Telecommunications engineers establishing deep space communication

- Launch vehicle coordinators preparing the Atlas-Centaur rocket

- Ground operations controllers managing the mission from Earth.

Five Gifts to Humanity

Mariner 9’s achievements resonate through the decades. First, it became the first successful Mars orbiter, proving we could establish a permanent robotic presence around another planet. Second, it mapped most of the Martian surface with unprecedented detail, revealing a world of stunning geological complexity. Third, it discovered evidence of ancient water flows — those mysterious channels that whispered of a warmer, wetter Mars. Fourth, it provided our first detailed study of the Martian moons, Phobos and Deimos, expanding our understanding of small celestial bodies. Fifth, it demonstrated that long-duration interplanetary missions were possible, paving the way for every Mars mission that followed.

The Ripple Effect

Imagine if Mariner 9 had failed. Would we have the rovers — Sojourner (1997), Spirit (2004–2010), Opportunity (2004–2018), Curiosity (2012–present), and Perseverance (2021–present) — exploring Martian soil? Would we still dream of human colonies on the Red Planet? Would countless young minds have been inspired to pursue careers in science and engineering? The mission’s success created a cascade of possibility that continues to shape our technological vision of space exploration.

Back to you…

I’ve worked with a long list of folks whose story involved technical achievements, from scientists to engineers and entrepreneurs. While digging below the surface we invariably discover a cast of supporting characters that made their project a success. If your story involves a team effort, weaving bits of their stories is one way to add depth and richness to your story.

◆

contact me to discuss your storytelling goals!

◆

Subscribe to the newsletter for the latest updates!

Copyright Storytelling with Impact® – All rights reserved